Lupus has been described as an illness of modern times. However, articles describing what we now know as Lupus can be traced back to the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates.

Hippocrates was born in 460 BC and his name is the origin of the 'Hippocratic Oath', which all modern doctors still adhere to. Hippocrates wrote about the severe red facial rash which we now recognise as a classic symptom of Lupus.

The word Lupus is Latin for Wolf. There are conflicting accounts for the origin of the term Lupus, which was first coined by the physician Rogerius in the 1200s, who used it to describe erosive facial lesions. According to one account, the distinctive butterfly rash associated with Lupus resembles the bite marks of a wolf attack. The other theory says that the frightening facial marks on people's faces were similar to the distinctive marks on a wolf's face.

Lupus in the 1800s

Research on Lupus in western medicine began in earnest in the 19th century. In the mid 1800s, leading Viennese physicians Ferdinand von Hebra and his son-in-law Moritz Kaposi wrote the first treatises recognising that the symptoms of Lupus extended beyond the skin and affected the organs of the body too.

Moriz Kaposi

In 1894, Dr Thomas Payne, a physician in St. Thomas' Hospital London, recognised that chloroquine might have more general healing powers in lupus, for example to treat joint pain & fatigue. This discovery paved the way for a century of 'antimalarial' use in various forms of lupus.

The term "lupus erythematosus" was first used in 1851 by a French physician named Pierre Cazenave. "Lupus" is the Latin word for "wolf," and "erythema" is the Greek word for "redness" or "blush." As physicians saw more of the disease and understood more about it, Moriz Kaposi used the terms "lupus disseminated" and "lupus discoid" for the first time in the mid-1800s to describe the skin disorders.

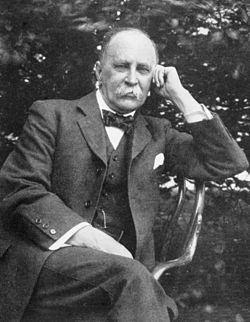

Sir William Osler

Between 1895 and 1903 Canadian physician Sir William Osler wrote the first complete treatises on lupus erythematosus. For the first time he showed that, in addition to classic symptoms such as fevers and aching, the central nervous system, muscles, skeleton, heart and lungs could potentially be part of the disease.

Dr Osler also identified that lupus could be 'systemic' i.e. that it could affect the entire body, not just one part. He also noted how lupus could relapse, and then 'flare' some months later periodically.

Lupus in the 20th Century

In the 1920s and 30s work began on defining a pathological (disease-oriented) description of Lupus. A major breakthrough came in 1941 when pathologists at the Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City wrote detailed pathological descriptions of lupus. Dr Paul Klemperer and his colleagues coined the term "collagen disease", which led ultimately to our modern classification of lupus as an autoimmune disorder.

In 1946 Dr Malcolm Hargraves, a pathologist from the renowned Mayo clinic published a description of the lupus erythematosus or LE cell. This important development identified the systemic inflammatory part of the disease, and allowed doctors to diagnose the disease faster and with greater reliability.

Dr Philip Hench

In 1949, also at the Mayo Clinic, physician Dr Philip Hench demonstrated that a newly discovered hormone called cortisone that could treat rheumatoid arthritis. Cortisone was used to treat SLE patients and immediately showed a dramatic ability to save lives.

In the 1950s the LE cell was shown to be part of the ANA (antinuclear antibody) reaction. This led directly to the development of a series of tests for antibodies, which allowed doctors and researchers to identify and define the disease in a more rigorous way. These are the so called 'fluorescent tests', which detect the antibodies that attack the nucleus of cells - the ANA.

Further research on antibodies established that the blood of lupus patients have other antibodies present. Some of these were found to bind to the DNA itself (DNA is the unique strand of proteins that are the 'blueprint' which the body uses to build and maintain itself). This ultimately led to a test for the anti-DNA antibodies themselves, which has proved to be one of the best tests available for diagnosing SLE. The anti-DNA test for SLE is still used widely today. There are now a wide variety of other antibody tests used in clinical practice and these are useful in subsetting patients in order to give the best advice especially when planning pregnancy.

9th March 2011 Benlysta (Bellumimab), the first new treatment developed to treat systemic lupus in over 50 years, was approved by the FDA (US Food & Drug Administration).

Benlytsa is the first in a new class of drugs called BLyS-specific inhibitors, which work by targeting a naturally occurring protein believed to play a role in the production of antibodies which attack and destroy the body's own healthy tissues. It was developed by Human Genome Sciences, a biotechnology company based in Rockville, Maryland, together with London-based pharmaceutical company GSK (GlaxoSmithKline).

NICE. (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence ) would not approve the use of the drug in the UK on cost grounds until May 2016 when Benlysta was approved by NICE for limited use in the NHS. NICE guidelines say treatment with Benlysta can be funded by the health service, for patients meeting specific criteria under a managed access agreement between GSK and NHS England, which will provide the drug at a discounted price and on the condition that data is collected to help address remaining questions over its efficacy.

In November 2017 GSK received FDA approval for a single-dose prefilled pen (autoinjector) presentation, administered as a once weekly subcutaneous injection of 200mg. This enables patients to self-administer their medicine at home, after initial supervision from their clinical team if considered appropriate. The subcutaneous version of the medicine adds to the existing intravenous (IV) formulation, but it is not yet available in the UK.